From The Archives: Gymnasiad (1744 epic poem)

With the Prologomena of Scriblerus Tertius, and notes varorium.

In my searches on the wonderful Internet Archive I came across this very short, but very curious epic poem: Gymnasiad. The title page has the Latin phrase Nos haec novimus esse nihil (tr. We know these things to be nothing) and tells us that this poem was "Written by the E—l of C———d". Presumably a joke because the internet tells me it was actually written by satirical writer Paul Whitehead (1710-1774), whose biography on the British Museum's website reads:

1739, arrested for his anti-Walpole satire "Manners"; 9 March 1741 and again in 1742, with Esquire Carey, surgeon to the prince of Wales, organized a mock Masonic procession along the Strand; mid 1740s imprisoned for debt; from the 1750s one of the "Medmenham Monks" (see entry for Francis Dashwood); through Dashwood's patronage appointed to two sinecures, secretary to the treasurer of the chamber at £800 p.a. (1761) and, deputy wardrobe keeper to the king (1763). Friend and supporter of William Hogarth.

"Scriblerus Tertius", credited with writing the tertiary scribbles, is apparently a pseudonym for Thomas Cooke (1703-1756). There is more context but I'll provide that after the poem at the bottom of the page. For now, just read on blindly like I did. Except unlike when I read it, somebody went through the trouble of making some minor spelling updates including changing all instances of the archaic ' ſ ' (long s) to the sleek & modern ' s '. And that same somebody also seamlessly inserted the original notes varorium with the latest footnotes technology![[0]] Like all good poems, it starts with an address and an introduction.

[[0]]:Shout-out Spectral Web Services for the code

THE GYMNASIAD: Or, Boxing-Match.

TO THE Most Puissant and Invincible Mr. John Broughton.

HAD this Dedication been addressed to some Reverend Prelate or Female Court Favourite, to some Blundering Statesman, or Apostate Patriot, I should doubtless have launched into the highest Encomiums on Public Spirit, Policy, Virtue, Piety, &c. and, like the rest of my Brother Dedicators, had most successfully imposed on their Vanity, by ascribing to them Qualities they were utterly unacquianted with, by which Means I had prudently reaped the Reward of a Panegyrist from my Patron, and, at the same time, secured the Reputation of a Satirist with the Public.

But scorning these base Arts; I present the following Poem to you, unswayed by either Flattery or Interest; since your Modesty would defend you against the Poison of the one, and your known Economy prevent an Author's Expectations of the other. I shall therefore only tell you, what you really are, and leave those (whose Patrons are of the higher Class) to tell them what they really are not. But such is the Depravity of human Nature, that every Compliment we bestow on another, is too apt to be deemed a Satire on ourselves; yet surely while I am praising the Strength of your Arm, no Politician can think it meant as a Reflection on the Weakness of his Head, or while I am justifying your Title to the Character of a Man, will any modern Petit-Maître think it an Impeachment of his Affinity to that of its mimic Counterfeit, a Monkey.

Were I to attempt a Description of your Qualifications, I might justly have Recourse to the Majesty of Agamemnon, the courage of Achilles, the Strength of Ajax, and the Wisdom of Ulysses; but as your own heroic Actions afford us the best Mirror of your Merits, I shall leave the reader to view in that the amazing Lustre of a Character, a few Traits of which only, the following POEM was intended to display; and in which had the Ability of the Poet equalled the Magnanimity of his Hero, I doubt not but the GYMNASIAD had, like the immortal ILIAD, been handed down to the Admiration of all Posterity.

As your superior Merits contributed towards raising you to the Dignities you now enjoy, and place you even as SAFE-GUARD of Royalty itself, so I cannot help thinking it happy for the Prince, that he is now able to boast one real Champion in his Service: And what Frenchman would not tremble more at the puissant Arm of a BROUGHTON, than at the ceremonious Gauntlet of a DIMMACK.

I am,

with the most profound Respect

to your HEROIC VIRTUES,

your most devoted,

most obedient, and

most humble Servant.

Scriblerus Tertius OF THE POEM

IT is an old Saying, that Necessity is the Mother of Invention; it should seem then that Poetry, which is a Species of Being, must naturally derive its Being from the same Origin; hence it will be easy to account for the many flimsy Ghost-like Apparations that every Day make their Appearance among us; for if it be true, as Naturalists observe, that the Health and Vigour of the Mother is necessary to produce the like Qualities in their Child, What Issue can be expected from the Womb of so meagre a Parent?

But there is another Species of Poetry, which instead of owing its Birth to the Belly, like Minerva, springs at once from the Head; of this Kind are those Productions of Wit, Sense, and Spirit, which once born, like the Goddess herself, immediately becomes immortal. It is true these are a Sort of miraculous Births, and therefore it is no Wonder they should be found so rare among us. — As Glory is the noble Inspirer of the latter, so Hunger is the natural Incentive of the former; thus Fame and Food are the Spurs with which every Poet mounts his Pegasus; but as the Impetus of the Belly is apt to be more cogent than that of the Head, so you will ever see the one pricking and goading a tired Jade to a hobling Trot, while the other only incites the foaming Steed to a majestic Capriol.

The gentle Reader, it is apprehended, will not long be at a Loss to determine, which Species the following Production ought to be ranked under; but as the Parent most unnaturally cast it out as the spurious Issue of his Brain, and even cruelly denies it the common Privilege of his Name, struck with the delectable Beauty of its Features, I could not avoid adopting the little poetic Orphan, and by dressing it up with a few Notes, &c. present it to the Public as perfect as possible.

Had I, in Imitations of other great Authors, only consulted my Interest in the Publications of this inimitable Piece (which doubtless will undergo numerous Impressions) I might first have sent it into the World naked; then by the Addition of a Commentary, Notes Variorum, Prolegomena, and all that, levied a new Tax upon the Public; and after all by a Sort of modern poetical Legerdemain, changing the Name of the principal Hero, and inserting a few Hypercritics, of a flattering Friend's, have rendered the former Editions incorrect, and cozened the curious Reader out of a treble Consideration for the same Work; but however this may suit the tricking Arts of a Bookseller, it is certainly much below the sublime Genius of an Author. — I know it will be said that a Man has an equal Right to make as much as he can of his Wit, as well as of his Money; but then it ought to be considered, whether there may not be such a Thing as Usury in both, and the Law having only provided against it in one Instance, is, I apprehend, no very moral Plea for the Practice of it in the other.[[1]]

The judicious Reader will easily perceive that the following Poem, in all its Properties, partakes of the Epic; such as fighting, speeching, bullying, ranting, &c. (to say Nothing of the Moral) and as many thousand Verses are thought necessary to the Construction of this kind of Poem, it may be objected, that this is too short to be ranked under that Class; to which I shall only answer, that as Conciseness is the last Fault a Writer is apt to commit, so it is generally the first a Reader is willing to forgive; and though it may not be altogether so long, yet I dare say, it will not be found less replete with the true Vis poetica, that (not to mention the Iliad, Aeneid, &c.) even Leonidas itself.

It may farther be objected that the Characters of our principal Heroes are too humble for the Grandeur of the Epic Fable; but the candid Reader will be pleased to observe, that they are not here celebrated in their mechanic, but in their heroic Capacities, as Boxers, who, by the Ancients themselves, have ever been esteemed worthy to be immortalized in the noblest Works of this Nature; of whih the Epeius and Euryalus of Homer, and the Entellus and Dares of Virgil, are incontestable Authorities. And as those Authors were ever careful, that their principal Personages, (however mean in themselves) should derive their Pedigree from some Deity, or illustrious Hero, so our Author has with equal Propiety made his spring from Phaethon and Neptune; under which Characters, he beautifully allegorizes their different Occupations of Waterman, and Coachman. — But for my own part, I cannot conceive, that the Dignity of the Hero's Procession, is any ways essential to that of the Action; for it is the greatest Persons are guilty of the meanest Actions, why may not the greatest Actions be ascribed to the meanest Persons.

As the main Action of this Poem is entirely supported by the principal Heroes themselves, it has been maliciously insinuated to be designed as an unmannerly Refletion on a late glorious Victory, where it is pretended, the whole Action was achieved without the Interposition of the principal Heroes at all. — But as the most innocent Meanings may, by ill Minds, be wrested to the most wicked Purposes, if any such Construction should be made, I will venture to affirm that it must proceed from the factious Venom of the Reader, and not from any disloyal Malignity in our Author, who is too well acquainted with the Power, ever to arraign the Purity of Government; besides the Poignance of the Sword is too prevalent for that of the Pen; and who, when there are at present, so many thousand unanswerable standing Arguments ready to defend, would ever be Quixote enough to attack, either the Omnipotence of a Prince, or the Omniscience of his Ministers?

Were I to attempt an Analysis of this Poem I could demonstrate that it contains (as much as a Piece of so sublime a Nature will admit of) all those true Standards of Wit, Humour, Railery, Satire, and Ridicule, which a late Writer has so marvelously discovered; and might, on the Part of our Author, say with that profound Critic, — iacta est alea: but as the Obscurity of a Beauty too strongly argues the Want of one, so an Endeavour to elucidate the Merits of the following Performance, might be apt to give the Reader a disadvantageous Impression against it, as it might tacitly imply they were too mysterious to come within the Compass of his Comprehension; I shall thereore leave them to his more curious Observation, and bid him heartily Farewell — Lege & delectate.

SCRIBLERUS TERTIUS

[[1]]:As this may be thought to be particulaly aimed at an Author who is lately dead, (and whose Loss, all Lovers of the Muses have the greatest Reason to lament) it may not be improper to assure the Reader, that it was written, and intended to have been published, before that Author's Decease, and was only meant, as an Attack upon the general Abuse of this Kind. — As to our Author himself, he has frequently given public Testimonies of his Veneration for that great Man's Genius, nor may it be unentertaining to the Reader, to acquaint him with one private Instance. — Immediately on hearing the Report of Mr. Pope's Death, he was heard to break forth in the following Exclamation.

POPE dead! – Hush, Hush REPORT, the sland'rous Lie,

FAME says he lives, — Immortals never die.

THE GYMNASIAD

BOOK I.

The ARGUMENT.

The Invocation, the Proposition, the Night before the Battle described; the Morning opens, and discovers the Multitude basting to the Place of Action; their various Professions, Dignities, &c. illustrated; the Spectators being seated, the youthful Combatants are first introduced, their Manner of Fighting displayed; to these succeed the Champions of a higher Degree, their superior Abilities marked, some of the most Eminent particularly celebrated; meanwhile, the principal Heroes are represented fitting, and ruminating on the approaching Combat, when the Herald summons them to the Lists.

SING, sing, O Muse, the dire contested Fray,

And bloody Honours of that dreadful Day,

When Phaethon's bold Son (tremendous Name)

Dared Neptune's Offspring to the Lists of Fame; [[2]]

What Fury fraught Thee with Ambition's Fire?

Ambition, equal Foe to Son and Sire:[[3]]

One, hapless fell by Jove's etherial Arms,

And One, the Triton's mighty Power disarms,

Now all lay hushed within the Folds of Night,

And saw in painted Dreams the important Fight;

While Hopes and Fears alternate turn the Scales,

And now this Hero, and now that prevails;

Blows and imaginary Blood survey,

Then waking, watch the slow Approach of Day.

When, lo! Aurora in her saffron Vest,

Darts a glad Ray, and gilds the ruddy East.

Forth issuing now all the ardent seek the Place,

Sacred to Fame, and the Athletic Race;

As from their Hive the clustering Squadrons pour,

Over fragrant Meads to sip the vernal Flower;

So from each Inn the legal Swarms impel,[[4]]

Of banded Seers, and Pupils of the Quill.

Senates and Shambles pour forth all their Store,

Mindful of Mutton, and of Laws no more;[[5]]

Even Money Bills, uncourtly, now must wait,

And the fat Lamb has one more day to bleat.

The Highway Knight now draws his Pistol's Load,

Rests his faint Steed, and this Day franks the Road.[[6]]

Bailiffs, in Crowds, neglect the dormant Writ,

And give another Sunday to the Wit;

He too would hie, but, ah! his Fortunes frown,

Alas! the fatal Passport's — Half a crown.

Shoals press on Shoals, from Palace and from Cell,

Lords yield the Court, and Butchers Clerkenwell.

St. Giles's Natives, never known to fail,

All who haply escaped th' obdurate Jail;

There many a martial Son of Tott'nham lies,[[7]]

Bound in Develian Bands, a Sacrifice

To angry Justice, nor must view the Prize.

Assembled Myriads crowd the circiling Seats,

High for the Combat every Bosom beats,

Each Bosom partial for its Hero bold,

Partial through Friendship, — or depending Gold.

But first, the Infant Progeny of Mars[[8]]

Join in the Lists, and wage their Pigmy Wars;

Trained to the manual Fight, and bruiseful Toil,

The Stop defensive, and gymnastic Foil;

With nimble Fists their early Prowess show,

And mark the future Hero in each Blow.

To these, the hardy iron Race succeed,

All Sons of Hockley and fierce Brick-street Breed;[[9]]

Mature in Valour, and inured to Blood,

Dauntless each Foe, in Form terrific, stood;

Their callous Bodies frequent in the Fray,

Mocked the fell Stroke, nor to its Force gave way.

Amongst these Gloverius, not the last in Fame;

And he whose Clog delights the beautous Dame;[[10]]

Nor least thy Praise whose artificial Light,[[11]]

In Dian's Absence, gilds the Clouds of Night.

While these the Combat's direful Arts display,

And share the bloody Fortunes of the Day,

Each Hero sat revolving, in his Soul,

The various Means that might his Foe control;

Conquest and Glory each proud Bosom warms,

When, lo! the Herald summons' them to Arms.

[[2]]:[When Phaeton's bold Son / Dared Neptune's Offspring] It is usual for Poets to call the Sons after the Names of their Fathers, as Agamemnon, the Son of Atreus, and Achilles the Son of Peleus, are frequently termed Pelides and Atrides; our Author would doubtless have followed this laudable Example, but he found Broughtonides and Stephensonides, or their Contractions, too unmusical for Metre, and therefore with wonderful Art adopts two poetical Parents, which obviates the Difficulty, and at the same Time heightens the Dignity of his Heroes.

Bentleides.

[[3]]:[Ambition equal Foe to Son and Sire:] It has been maintained by some Philosophers, that the Passions of the Mind are in some measure hereditary, as well as the Features of the Body, according to this Doctrine, our Author beautifully represents the Frailty of Ambition descending from Father to Son, — and as Original Sin may in some Sort be accounted for on this System, it is very probably our Author had a theological, as well as a physical, and moral Meaning in this Verse.

For the latter Part of this Note, we are obliged to an eminent Divine.

[[4]]:[legal Swarms impel,] An ingenous Critic of my Acquiantance objected to this Simile, and would, by no means, admit the Comparison between Bees and Lawyers to be just; one, he said, was an industrious, harmless, and useful Species, none of which Properties could be affirmed of the other, and therefore he thought the Drone that lives on the Plunder of the Hive a more proper Archetype. I must confess myself in some Measure inclined to subscribe my Friend's Opinion; but then we must consider, that our Author did not intend to describe their Qualities, but their Number, and in this Respect no one, I think, can have any Objection to the Propiety of the Comparison.

[[5]]:[and of Laws no more] The original M.S. has it, Bribes, but as this might seem to cast an invidious Aspersion on a certain Assembly, remarkable for their Abhorrence of Venality; and, at the same Time, might subject our Publisher to some little Inconveniencies, I thought it prudent to soften the Expression; besides, I think this Reading renders our Author's Thought more natural; for though we see the most trifling Avocations are able to draw off their Attention from the public Utility, yet nothing is sufficient to divert a steady Pursuit of their private Emolument.

[[6]]:[this Day franks the Road.] Our Poet here artfully insinuates the Diginity of the Combat, he is about to celebrate, by its being able to prevail on a Highwayman to lay aside his Business to become a Spectator of it ——— and as, on this Occasion, he makes him forsake his daily Bread, while the Senator only neglects the Business of the Nation, it may be observed, how satirically he gives the Preference in point of Disinterestedness to the Highwayman.

[[7]]:[There many a martial Son, &c.] The unwary Reader may from this Passage be apt to conclude, that an Amphitheatre is little better than a Nursery for the Gallows, and that there is a Sort of physical Connection between Boxing and Thieving; but although Boxing may be a useful Ingredient in a Thief, yet it does not necessarily make him one; Boxing is the Effect, not the Cause; and Men are not Thieves because they are Boxers, but Boxers because they are Thieves. Thus Tricking, Lying, Evasion (with several other such like cardinal Virtues,) are a Sort of Properties pertaining to the Practice of Law, as well as to the mercurial Profession. But would any one therefore infer that every Lawyer must be a Thief.

Scholiast.

[[8]]:*[infant Progeny of Mars] Our Author in this Description alludes to the Lusus Troiae of Virgil,

Incendunt Pueri —————–———————–—–———————–——–——–————–—–———–————–—–——Troiaeque iuventus——————Pugnaeque cient simulacra sub armis.

[[9]]:[Hockley and fierce Brickstreet Breed.] Two famous Athletic Seminaries.

[[10]]:[And he whose Clog, &c.] Here we are presented with a laudable Imitation of the ancient Simplicity of Manners; for as Cincinattus disdained not the homely Employment of a Ploughman, so we see our Hero condescending to the humble Occupation of Clog-Maker; and this is the more to be admired, as it is one Characteristic of modern Heroism to be either above or below an Occupation at all.

[[11]]:[whose artificial Light,] Various and violent have been the Controversies, whether our Author here intended to celebrate a Lamp-Lighter, or a Link-boy; but as there are Heroes of both Capacities at present in the School of Honour, it is difficult to determine, whether the Poet alludes to a Wells or a Buckhorse

THE GYMNASIAD

BOOK II.

The ARGUMENT.

STEPHENSON enters the Lists; a Description of his Figure; an Encomium on his Abilities, with respect to the Character of Coachman. BROUGHTON advances; his reverend Form described; his superior Skill in the Management of the Lighter and Wherry displayed; his Triumph of the Badge celebrated; his Speech; his former Victories recounted; the Preparation for the Combat, and the Horror of the Spectators. [[12]]

FIRST, to the Fight, advanced the Charioteer,

High Hopes of Glory on his Brow appear;

Terror vindictive flashes from his Eye;

(To one the Fates the visual Ray deny)

Fierce glowed his looks, which spoke his inward Rage,

He leaps the Bar, and bounds upon the Stage:

The Roofs re-echo with exulting Cries;[[13]]

And all behold him with admiring Eyes.

Ill-fated youth! what rash Desires could warm,

Thy manly Heart to dare the Triton's Arm?

Ah! too unequal to these martial Deeds,

Though none more skilled to rule the foaming Steeds:

The Coursers, still obedient to thy Rein,

Now urge their Flight, or now their Flight restrain.

Had mighty Diomed provoked the Race,

Thou far had'st left the Grecian in Disgrace:

Wherever you drove, each Inn confessed your Sway,

Maids brought the Dram, and Ostlers flew with Hay.

But know, though skilled to guide the rapid Car,[[14]]

None wages like thy Foe the manual War.

Now Neptune's Offspring dreadfully serene,

Of Size gigantic, and tremendous Mein,

Steps forth, and admidst the fated Lists appears,

Reverend his Form, but yet not worn with Years:

To him none equal, in his youthful Day,

With feathered Oar to skim the liquid Way;

Or through those Straits, whose Waters stun the Ear,

The loaded Light's buly Weight to steer.

Soon as the Ring their Ancient Warrior viewed,

Joy filled their Hearts, and thundering Shouts ensued;

Loud as when over Thamesis' gentle Flood,

Superior, with the Triton Youths he rowed,

While far ahead his winged Wherry flew,

Touched the glad Shore, and claimed the Badge its due.[[15]]

Then thus indignant he accosts the Foe,

(While high Disdain sat prideful on his Brow):

Long has the laurel Wreath victorious spread

Its sacred Honours round this hoary Head;

The Prize of Conquest in each doubtful Fray,

And dear Reward of many a dire-fought Day.

Now Youth's cold Wane the vigorous Pulse has chased,

Froze all my Blood, and every nerve unbraced;[[16]]

Now, from these Temples, shall the Spoils be torn,

In scornful Triumph by my Foe be worn?

What then avails my various Deads in Arms,

If this proud Crest thy feeble Force disarms?

Lost be my Glories to recording Fame,

When foiled by Thee, the Coward blasts my Name:

I, who e'er Manhood my young Joins had knit,

First taught the fierce Grettonius to submit;[[17]]

While drenched in Blood he, prostrate, pressed the Floor,

And inly groaned the fatal words — no more.

Allenius too, who every Heart dismayed,[[18]]

Whose Blows, like Hail, flew rattling round the Head;[[19]]

Him oft the Ring beheld, with weeping Eyes,

Stretched on the Ground, reluctant yield the Prize.

Then fell the Swain, with whom none ever could vie,[[20]]

Where Harrows' Steeple darts into the Sky.

Next the bold Youth, a bleeding lay,[[21]]

Whose waving Curls the Barber's Art display.

You too, this Arm's tremendous Prowess know,

Rash Man! to make this Arm again thy Foe.

This said — the Heroes for the Fight prepare,[[22]]

Brace their big Limbs and brawny Bodies bare.

The sturdy Sinews all aghast behold,

And ample Shoulders of atlean Mould;

Like Titan's Offspring, who against Heaven strove;

So each, though mortal, seemed a Match for Jove.

Now round the Ring a silent Horror reigns,

Speechless each Tongue, and bloodless all their Veins.

When lo! the Champions give the dreadful Sign,

And Hand in Hand in friendly token join;

Those iron Hands, which soon, upon the Foe,

With giant Force, must deal the deathful Blow.

[[12]]:[Argument] It was doubtless in Obedience to the Custom, and the Example of other great Poets, that our Author has thought proper to prefix an Argument to each Book, being minded that nothing should be wanting in the usual Paraphernalia of Works of this Kind. —— For my own Part, I am at a Loss to account for the Use of them, unless it be to swell a Volume, or, like Bills of Fare, to advertise the Reader what he is to expect, that if it contains nothing likely to suit his Taste, he may preserve his Appetite for the next Course.

[[13]]:[He leaps the Bar, / The Roofs re-echo] See the Descriptions of Dares in Virgil,

Nec mora: continuo vastis cum viribus effert

Ora Dares, magnoque virum se murmure tollit;

[[14]]:[But know, though Skilled] Here our Author inculcates a fine Moral, by showing how apt Men are to mistake their talents; but were Men only to act in their proper Spheres, how often should we see the Parson in the Pew of the Peasant, the Author in the Character of his Hawkers, or a Beau in the Livery of his Footman, &c.?

[[15]]:[the Badge its due.] A Prize given by Mr. Dogget to be annually contested on the first Day of August, —— as among the Ancients, Games and Sports were celebrated on mournful as well as joyful Events, there has been some Controversy whether our loyal Comedian meant the Compliment to the setting or rising Monarch of that day; but, as the Plate has a Horse for its Device, I am induced to impute it to the latter; and, doubtless, he prudently considered, that as a living Dog is better tha a dead Lion, the living Horse had, at least, an equal Title to the same Preference.

[[16]]:[Froze all my Blood,] See Virgil.

———Sed enim gelidus tardante seneca

Sanguis hebet, frigentue effaetae in corpore vires.

[[17]]:[Fierce Grettonius to submit] Gretton, the most famous Athleta, in his Days, over whom our Hero obtained his maiden Prize.

[[18]]:[Allenius too, &c.] Vulgarly known by the plebeian Name of Pipes, which a learned Critic will have to be derived from the Art and Mystery of Pipe-Making, in which, it is affirmed, this Hero was an Adept. ——As he was the Delicium pugnacis generis, our Author, with marvellous Judgement, represents the Ring weeping at his Defeat.

[[19]]:[Whose Blows like Hail, &c.] Virgil.

———quam multa grandine nimbi

Culminibus crepitant.———

[[20]]:[Then fell the Swain] Jeoffery Birch, who, in several Encounters, served only to Augment the Number of our Hero's Triumphs.

[[21]]:[Next the bold Youth] As this Champion is still living, and even disputes the Palm of Manhood with our Hero himself, I shall leave him to be the Subject of Immortality in some future Gymnasiad, should the Superiority of his Prowess every justify his title to the Corona Pugnea.

[[22]]:[This said, &c.] Virgil.

Haec fatus, duplicem ex Humeris rejecit Amictum;

Et magnos Membrorum, magna ossa lacertosque Exuit.

THE GYMNASIAD

BOOK III.

The ARGUMENT.

A Description of the Battle; STEPHENSON is vanquished; the Manner of his Body being carried off by his Friends; BROUGHTON claims the Prize, and takes his final Leave of the Stage.

FULL in the Center now they fix in Form,

Eye meeting Eye, and Arm opposed to Arm;

With wily Feints each other now provoke,

And cautious meditate the impending Stroke.

The impatient Youth, inspired by Hopes of Fame,

First sped his arm, unfaithful to its Aim;

The wary Warrior, watchful of his Foe,[[23]]

Bends back, and escapes the death-designing Blow;

With erring Glance it sounded by his Ear,

And whizzing spent its idle Force in Air.[[24]]

Then quick advancing on the unguarded Head,

A dreadful Shower of Thunderbolts, he shed;

As when a Whirlwind, from some Cavern broke,

With furious Blasts assaults the monarch Oak,

This Way and that its lofty Top it bends,

And the fierce Storm the crackling Branches rends:

So waved the Head, and now to left and right

Rebounding flies, and crashed beneath the Weight.

Like the young Lion wounded by a Dart,[[25]]

Whose Fury kindles at the galling Smart;

The Hero rouzes with redoubled Rage,

Flies on his Foe, and foams upon the Stage.

Now grappling, both in close Contention join,

Legs lock in Legs, and Arms in Arms entwine;[[26]]

They sweat, they heave, each tugging Nerve they strain,

Both fixed as Oaks, their sturdy Trunks sustain.

At length the Chief his wily art displayed,

Poised on his Hip the hapless Youth he laid;

Aloft in Air his quivering Limbs he throwed,

Then on the Ground down dashed the ponderous Load.

So some vast Ruin on a Mountain's Brow,

Which tottering hangs, and dreadful nods below,

When the fierce Tempest the Foundation rends,

Whirled through the Air with horrid Crush descends.

Bold and undaunted up the Hero rose,[[27]]

Fiercer his Bosom for the Combat glows,

Shame stung his manly Heart, and fiery Rage

New steeled each Nerve, redoubled War to wage:

Swift to revenge the dire Disgrace he flies,

Again suspended on the Hip he lies;

Dashed on the ground, again had fatal fell,

Haply the Barrier caught his flying Heel;[[28]]

There fast it hung, the imprisoned Head gave way,

And the strong Arm defrauded of its Prey.

Vain strove the Chief to whirl the Mountain o'er;

It slipped ---- he headlong rattles on the Floor.

Around the Ring loud Peals of Thunder rise,

And Shouts exultant echo to the Skies.[[29]]

Uplifted now inanimate he seems,

Forth from his Nostrils gush the purple Streams;

Gasping for Breath, and impotent of Hand,

The Youth beheld his Rival staggering stand.

But he alas! had felt the unnerving Blow,

And gazed, unable to assault the Foe.

As when two Monarchs of the brindled Breed,

Dispute the proud Dominion of the Mead,

They fight, they foam, then wearied in the Fray,

Aloof retreat, and lowering stand at Bay.

So stood the Heroes, and indignant glared,

While grim with Blood their rueful Fronts were smeared,

’Till with returning Strength new Rage returns,

Again their arms are steeled, again each Bosom burns.

Incessant now their hollow Sides they pound, [[30]]

Loud on each Breast the bounding Bangs resound,

Their flying Fists around the Temples glow,

And the Jaws crackle with the massy Blow.

The raging Combat every Eye appalls,

Strokes following Strokes, and Falls succeeding Falls.

Now drooped the Youth, yet, urging all his Might,

With feeble Arm still vindicates the Fight;

’Till on the Part where heaved the panting Breath,

A fatal Blow impressed the Seal of Death;

Down dropped the Hero, weltering in his Gore,

And his stretched Limbs lay quivering on the Floor.

So when a Falcon skims the airy way,

Stoops from the Clouds, and pounces on his Prey;

Dashed on the Earth the feathered Victim lies,

Expands its feeble Wings, and fluttering dies.

His faithful Friends their dying Hero reared,[[31]]

Over his broad shoulders dangling hung his Head;

Dragging its Limbs, they bear the Body forth,

Mashed Teeth and clotted Blood came issuing from his Mouth.

Thus then the Victor — O Celestial Power!

Who gave this Arm to boast one Triumph more,

Now, grey in Glory, let my Labours cease,

My bloodstained Laurel wed the Branch of Peace,

Lured by the Lustre of the golden Prize,

No more in Combat this proud Crest shall rise;[[32]]

To future Heroes future Deeds belong,

Be mine the Theme of some immortal Song.

This said ---- he seized the Prize, while, round the Ring,

High soared Applause on Acclamations' Wing.

F I N I S.

[[23]]:[------------watchful of his Foe,

Bends back, and escapes the Death designing Blow;] Virgil

-------ille Ictum vienentem a vertice velox

Praevidit, celerique elapsus corpore cessit.

[[24]]:[its idle Force in Air.] Idem.

——vires in ventum effudit——

[[25]]:[Like the young Lion] It may be observed, that our Author has treated the Reader but wiht one Similie throughout the two foregoing Books, but in order to make him ample Amends, has given him no less than six in this. Doubtless this was in Imitation of Homer, and artfully intended to heighten the Dignity of the main Action, as well as as our Admiration towards the Conclusion of his Work. — Finis coronat Opus.

[[26]]:[Arms in Arms entwine;] Virgil.

Immiscentque manus manibus, pugnamque lacessunt.

[[27]]:[Bold and undaunted, &c.] Virgil

At non tardatus Casu, neque territus Heros,

Acrior ad pugnam redit, & Vim suscitat Ira.

Tum Pudor incendit Vires —————

[[28]]:[Haply the Barrier, &c.] Our Author, like Homer himself is no less to be admired in the Character of a Historian than in that of a Poet, we see him here faithfully reciting the most minute Incidents of the Battle and informing us, that the youthful Hero being on the Lock, must again inevitably have come to the Ground had not his Heel caught the Bar, and that his Antagonist, by the Violence of his training, slipped his Arm over his Head, and by that Means received the Fall he intended the Enemy —— I thought it incumbent on me as a Commentator to say thus much, to illustrate the Meaning of our Author, which might seem a little obscure to those who are unacquainted with Conflicts of this Kind.

[[29]]:[echo to the Skies, &c.] Virgil.

It Clamor Caelo————

The learned Reader will percieve our Author's frequent Allusions to Virgil, and whether he intended them as Translations or Imitations of the Roman Poet, must give us Pause; but as, in our modern Productions, we find Imitations are generally nothing more than bad Translations, and Translations nothing more than bad Imitations, it would equally, I suppose, satisfy the Gall of the Critic, should these unluckily fall within either Description.

[[30]]:[Incessant now, &c.] Virgil.

Multa Viri nequicquam inter Se vulnere jactant:

Multa cavo lateri ingeminant & pectore vastos

Dant sonitus, erratque aures & tempora circum

Crebra manus: duro crepitant sub vulnere Malae.

[[31]]:[His faithful Friends] Virgil.

Ast illum fidi AEquales, genua aegra trahentem,

Jactantemque utroque caput, crassumque cruorem

Ore ejectantem, mistosque ic sanguine dentes,

Ducunt ad naves———————

[[32]]:[No more in Combat, &c.] Idem.

———hic Victor caestus, artemque repons.

Back To Your Regularly Scheduled Programming

Pretty ebin, huh? Now, remember when I said "Written by the E—l of C———d" was presumably a joke because this was actually written by a satirist? It turns out my spidey sense was right. In 1777 (3 years after Paul Whitehead died), Captain Edward Thompson (1738-1786) published "The Poems and Miscellaneous Compositions of Paul Whitehead; with Explanatory Notes on his Writings, and his Life". In this book, he wrote that Gymnasiad "was written in ridicule of a brutish custom of Boxing". Who'd have thunk it?

It was a rebuke to Prince William Augustus (1721-1765), Duke of Cumberland (formerly an Earldom), who was known in his time as "The Butcher", which is always a terrible nickname for a military general and a fantastic nickname for a boxer. I don't know if the spare prince was a boxer, but he was an important patron of early boxing. One of the contemporary fighters he encouraged and financially backed was the most famous fighter of his day, Jack Broughton.

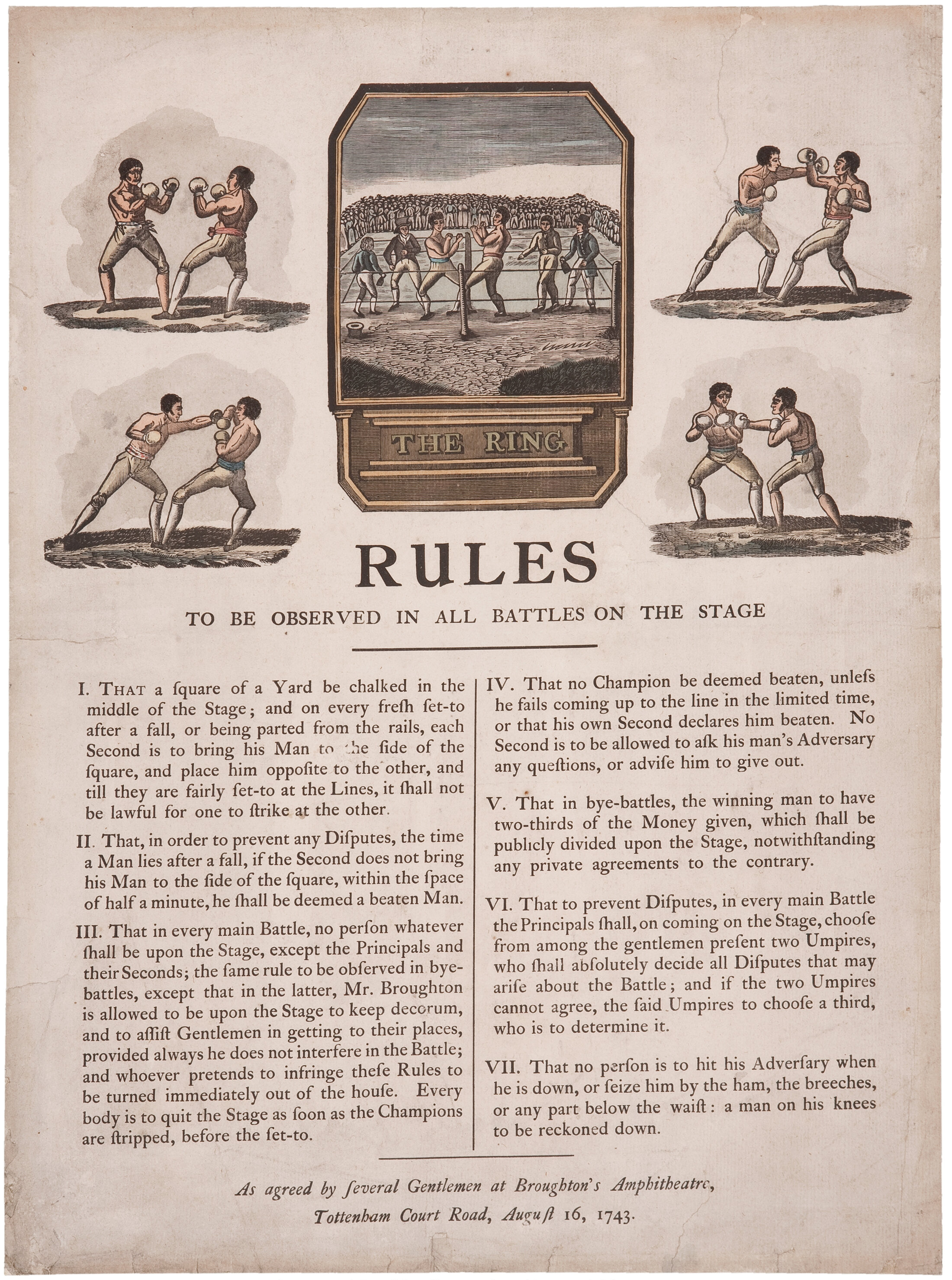

Known as the "Professor of Athletics" and "the father of the Prize Ring", Broughton is best remembered for the events of 1743. This was the year that he opened Broughton's New Amphitheatre (a boxing arena), invented 'mufflers' (the modern boxing glove), and is credited with writing what we still call Broughton's Rules (the first codified rules of boxing).

The mock epic is of course describing Jack Broughton's fight with "Coachman to a Nobleman" George Stephenson (sometimes spelled Stevenson). As far as I can tell, this 1746 account by Captain John Godfrey in A Treatise is one of the few contemporary sources for what happened in their fight as nearly all later sources repeat it nigh-verbatim.

I saw [George Stevenson, the coachman] fight BROUGHTON, for forty Minutes. BROUGHTON I knew to be ill at that Time; besides it was a hasty made Match, and he had not that Regard for his Preparation, as he afterwards found he should have. But here his true Bottom was proved, and his Conduct shone. They fought in one of the Fair-Booths at Tottenham Court, railed at the End toward the Pit. After about thirty-five Minutes, being both against the Rails, and scrambling for a Fall, BROUGHTON got such a Lock upon him as no Mathematician could have devised a better. There he held him by this artificial Lock, depriving him of all Power of Rising or Falling, till resting his Head for about three or four Minutes on his Back, he found himself recovering. Then loosed the Hold, and on setting to again, he hit the Coachman as hard a Blow as any he had given him in the whole Battle; that he could no longer stand, and his brave contending Heart, though with Reluctance, was forced to yield. The Coachman is a most beautiful Hitter; he put in his Blows faster than BROUGHTON, but then one of the latter's told for three of the former's. Pity - so much Spirit should not inhabit a stronger Body!

Godfrey's account was reproduced in Egan's Boxiana and Miles's Pugilistica in the 1800s, volume one of the latter even refers to him as "our perpetual resource, Captain Godfrey, whose thin quarto we must almost plead guilty to reprinting piecemeal". One other source of what happened in the fight is Gymnasiad. Yes, the above poem predates Godfrey's account by over two years.

Here's a chance for me to correct some very old misinformation. First of all, the picture above, Broughton's Rules. They're as phoney as a three-dollar bill. Or Chuck Jones's 1999 Coyote and Road Runner rules. The earliest written record of Broughton's rules appear in the November 1792 edition of The Sporting Magazine. It's stated that after establishing a monopoly with his new amphitheatre (fighters were "engaged by Broughton, under articles, to fight under no other stage"):

"Mr. Broughton being now constituted sole manager, began to think about the necessary laws and regulations for his stage: and accordingly, with the advice and approbation of several gentlemen, seven principal rules were drawn up; as these are not extant in any of the histories of boxing, we have carefully collected them for the gratification of our readers."

It then produces the rules seen in the picture above, complete with the claim that they were "as agreed to by several GENTLEMEN" alongside the date "August 16, 1743".

Over thirty years after The Sporting Magazine first wrote down the rules, 1823's Boxiana says that the rules were "approved of by the Gentlemen, and agreed to by the PUGILISTS, August 10, 1743" and 1841's Fistiana claim that the rules were "publicly propounded on the 18th of August, 1743". The slight difference in dates can be explained away with poor eyesight, damaged source material, or confusion stemming from the New Calendar Act of 1750. But "agreed to" and "publicly propounded" in 1743? By who? Where they at though?

When the New Rules (the London Prize Ring Rules) and Queensberry Rules eventually show up, they're referenced in contemporary writings such as books and newspapers. Meanwhile, Broughton's rules are not mentioned in his fairly well-documented career or in his obituaries. The first reference to them is nearly 4 years after his death, almost 50 years after they were alleged to have been written. These supposed rules are not mentioned by Captain Godfrey, they are not mentioned by Daniel Mendoza in The Art of Boxing (1792), and they are not mentioned in Thomas Fewtrell's Boxing Reviewed (1790). It can never be overstated that Wikipedia is an unreliable source of information.

I am hereby officially designating Broughton's Rules as cap until evidence proves that they existed in Broughton's lifetime.

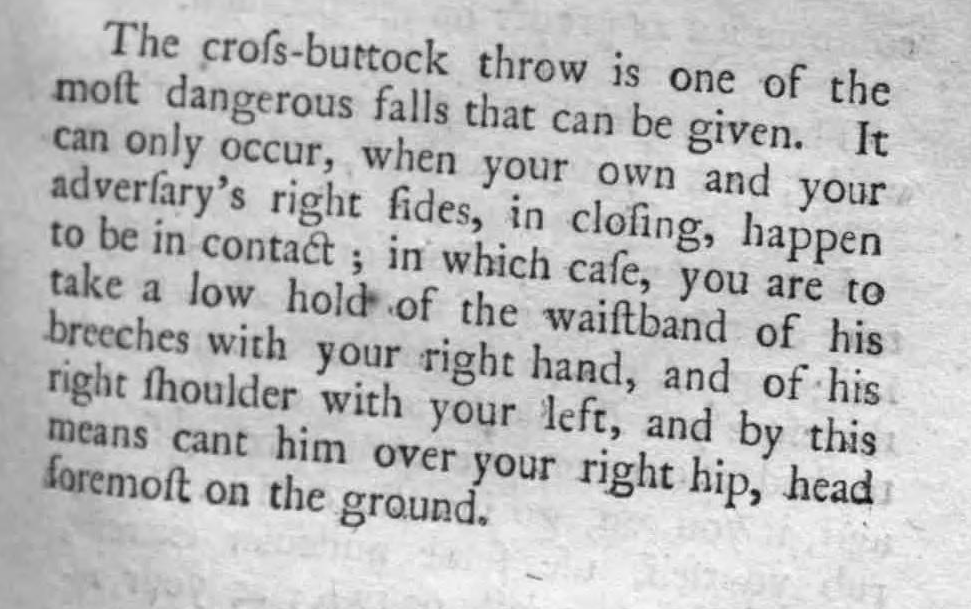

There are references in the 1700s to "the laws of boxing" but given how much boxing is being referred to as a science in that age, this is likely meant in the sense of uncodified but widely understood rules like the laws of nature or laws of the universe. These were essentially barely-regulated street fights which very slowly became less unregulated. For example, the lines in the poem about being poised or suspended on someone's hip aren't metaphors, they're descriptions of the cross-buttock. These are still bareknuckle fights so you couldn't land very many punches on someone's head without damaging your own hands, the meta - bar body blows, 'the chop' (landing a blow with the heel of your hand), and other modern fouls - was to vie for position to pick up an opponent using assorted wrestling locks and then slam them into the ground.

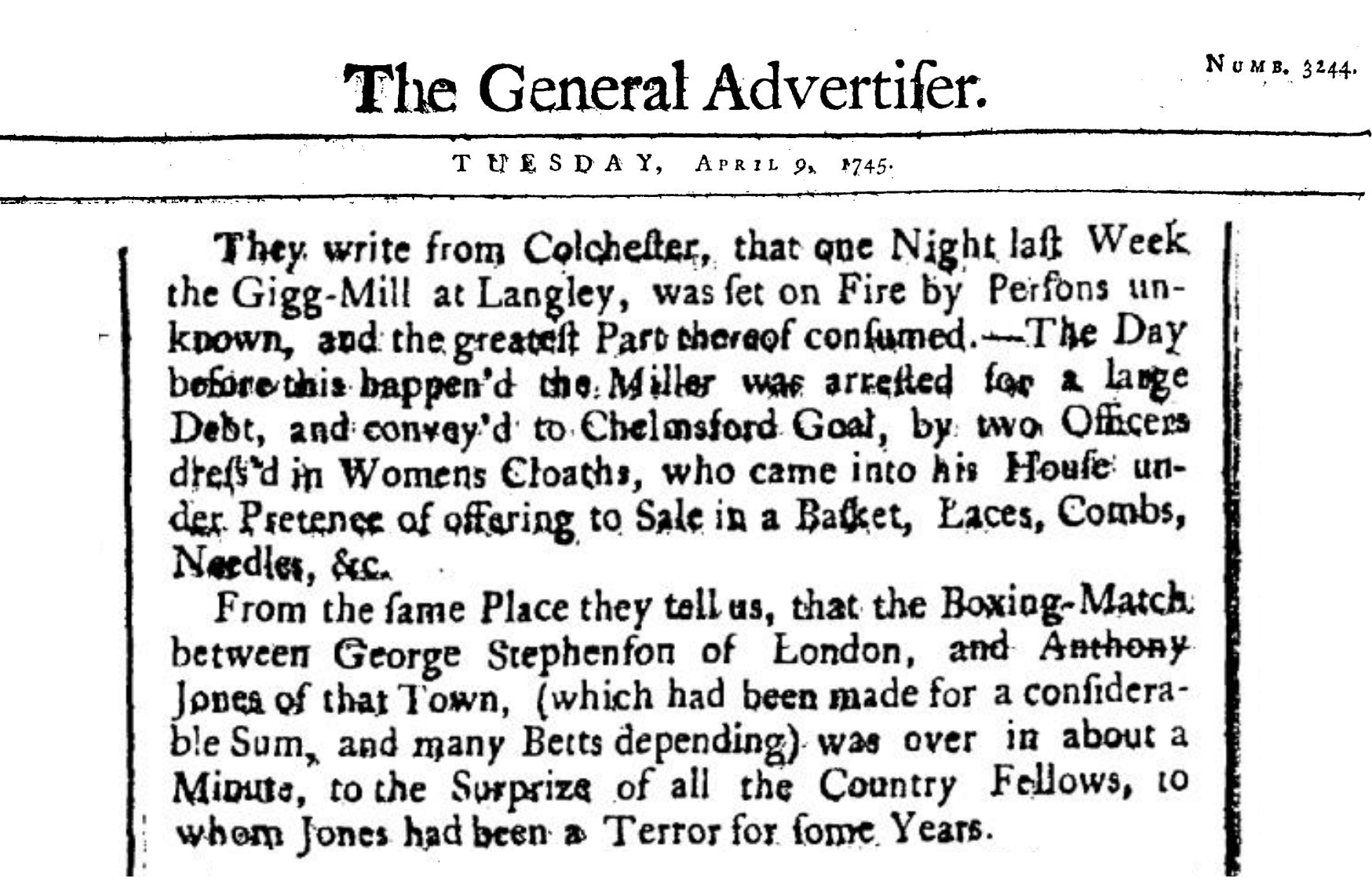

How can anyone believe the claim of several gentlemen agreeing to rewrite things wholesale when none of these gentlemen have ever been identified and none of their agreements have ever been recorded? Likewise, various sources claim that George Stephenson died after fighting Jack Broughton, and that his tragic death was what spurred the introduction of Broughton's Rules. This cannot be the case, because Stephenson was alive to fight in 1745:

"From the same Place they tell us, that the Boxing-Match between George Stephenson of London, and Anthony Jones of that Town, (which had been made for a considerable Sum, and many Betts depending) was over in about a Minute, to the Surprize of all the Country Fellows, to whom Jones had been Terror for some Years."

- The General Advertiser, April 9, 1745

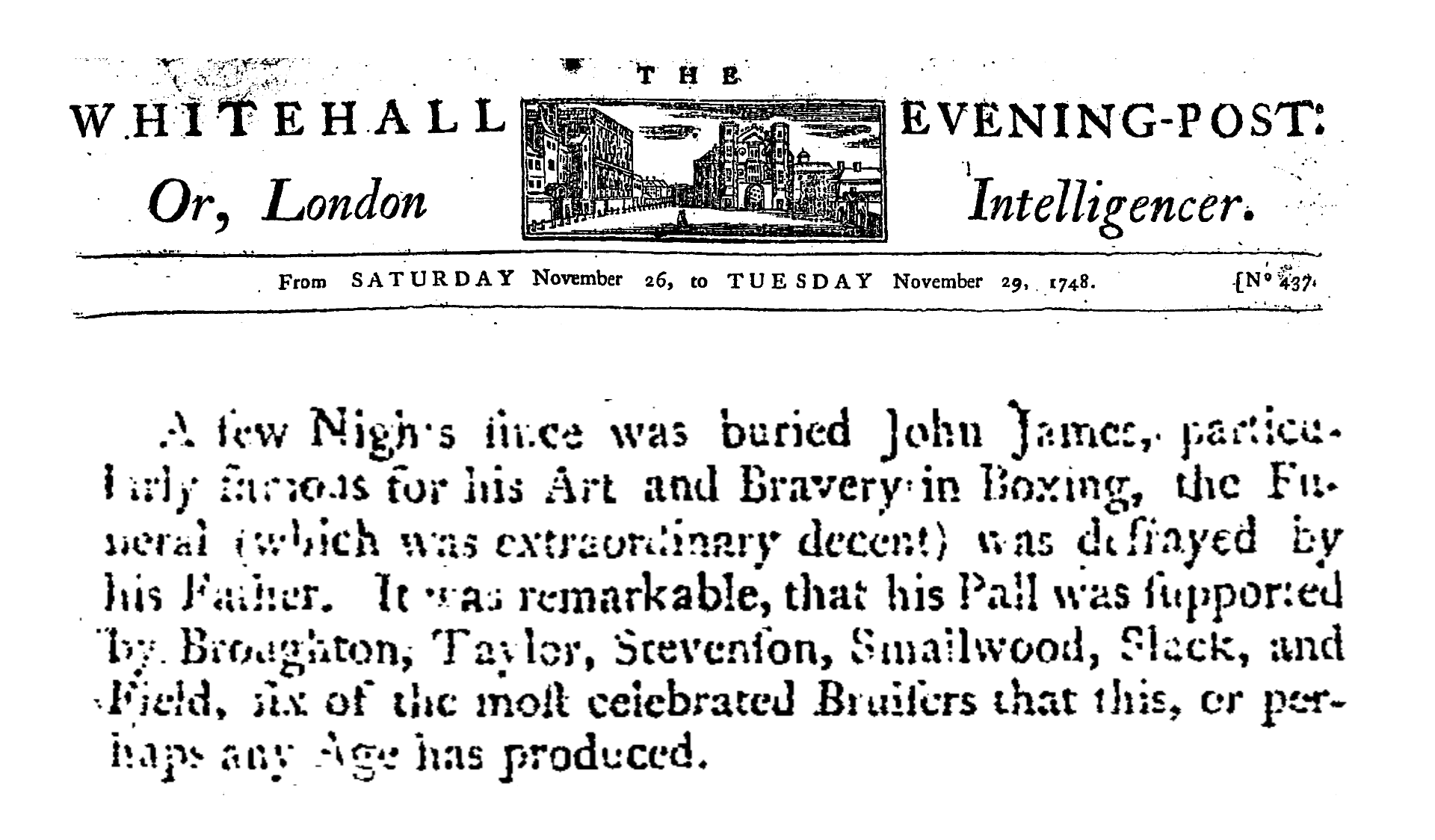

And he served as a pall-bearer at John James's funeral in 1748:

"A few Nights since was buried John James, particularly famous for his Art and Bravery in Boxing, the Funeral (which was extraordinary decent) was defrayed by his Father. It was remarkable, that his Pall was supported by Broughton, Taylor, Stevenson, Smallwood, Slack, and Field, six of the most celebrated Bruisers that this, or perhaps any Age has produced."

- Whitehall Evening Post, November 26, 1748 - November 29, 1748

Contrary to popular belief, we know for certain that Broughton and Stephenson actually had at least two fights. The first was on March 30th, 1738 "at the booth at Tottenham-Court" and the second was on April 24th, 1744 "At Broughton's Amphitheatre, near Tyburn-Road".[[36]]

The poem, on sale as early as June 1744, was almost certainly describing their second fight. The tagline "a very short, and very curious Poem" might be a reference to this being a fairly short fight for the era, lasting only "eight Minutes and a half." We'll never know for sure if Whitehead (and/or Cooke) were at the fight in person or relied on a second-hand account, but given how committed they were to trolling the powerful as well as the lovingly crafted details of the fight, my guess is that they attended.

Captain Godfrey's account identifies the location as Tottenham Court, meaning it's most likely a slightly misremembered telling of the 1738 fight, which lasted "16 Minutes and an Half" according to The Daily Post and "24 Minutes" according to The Daily Advertiser, both somewhat shorter than the 35-40 minutes Godfrey recalled years later. Though it's possible he may have been referring to a sparring session or an otherwise undocumented fight. The Notes Varorium of the poem (you did read them, right?) refer to "Gretton"[[33]] and "Pipes"[[34]], a couple of boxers that Broughton fought who are also mentioned in Godfrey's Treatise. There's also a reference to "Jeoffery Birch, who, in several Encounters, served only to Augment the Number of our Hero's Triumphs", we know Jeffery Birch (spellings vary) was a real person who fought Broughton at least once, so we can take the poem to be a reliable source of information. But neither Gymnasiad nor Godfrey say that Stephenson died after the fight. 1788's The Complete Art of Boxing (another text which cites "Captain Godfrey, in a publication which he gave under his name about forty years ago") also mentions Stephenson but does not mention his death.

So where did the confusion and misinformation come from? Well, we are talking about events that happened almost 300 years ago, it stands to reason that a lot of things have been lost to time since then. In the 1980s the art historian John Norman Sunderland (1942-2018) wrote about a painting of Broughton and Stephenson by John Hamilton Mortimer (1740-1779), claiming "the famous contest between Broughton and George Stevenson which took place in 1741" and "Further complexity arises from the fact that the fight between George Stevenson and Jack Broughton took place in February 1741." In fact, lots of 20th century newspapers, books, websites and auction houses refer to a fight between Broughton and Stephenson happening in February 1741. Who is responsible for this?

My research indicates we should blame Fred W. J. Henning, author of the 1902 book 'Fights for the Championship: The Men and Their Times Vol. I'. In it, Henning gives a stirring retelling of fights he never saw using the only sources available to him and claims that for Broughton vs. Stephenson "The date fixed for the battle was February, 1741", thereby entrenching the idea that they only fought once. On pages 26-33, Henning's version of the fight and its aftermath are so lively it leaps off the page, he's clearly a creative writer as he managed to spin Whitehead's poem and Godfrey's paragraph into a satisfying (and considerably longer) prose. The problems are that 1) he's limited by his times, and therefore doesn't have access to 21st-century technology that has made it easy to check 18th-century sources, and 2) he's taking a lot of creative liberty.

"On resuming, they stagger about like drunken men. Then Broughton closes with his antagonist, and holds him against the stake with such a grip that well-nigh crushes the life out of him. He does not attempt to throw him, though; but, suddenly releasing him, he steps back and, concentrating all his remaining strength, delivers a fearful blow right under the heart, and the brave Yorkshireman falls with a thud upon the platform, a senseless heap of humanity. A deathly pallor is upon his face, and the blood-marks over his chest and cheeks add to his ghastly appearance.

He does not move or breathe. Jack Broughton kneels at his side, and puts his hand to his naked breast. "Good God; what have I done?" he shouts. "I've killed him. So help me God, I'll never fight again!"

[...]

This was, however, not the case, for after remaining unconscious for several hours in a bedroom at the Adam and Eve Tavern, to which place he had been conveyed, the doctors observed symptoms of returning consciousness, and an examination was made. [...] The joyful news — especially to Jack Broughton — was speedily spread about that Stevenson lived, and many were the anxious inquiries on the following day at the hostelry where he lay. [...] It must have been a touching scene when the two men met again under such different and sad circumstances. "Master Broughton, is that you?" said the poor fellow as he extended his thin white hand. "They told me you had been asking for me. It is very good of you. You are kinder than you need have been. But I am glad, so very glad. Give me your hand, Jack."

And the Champion stayed a long while with poor George, cheering him considerably. Day after day he came and remained with him. But he got worse and worse, and then Jack Broughton would sit at the bedside, scarcely leaving him night or day. They became true friends, but that friendship was destined to be of but short duration, for within a month the injuries had a fatal termination, and the once fine specimen of an athlete passed quietly away, with his head resting peacefully upon the strong arm which had dealt him his death blow. [...] Therefore, we find about a year after Stevenson's death, Jack Broughton's 'Rules of the Ring' published,"

If this was written a century later, in the 2000s instead of the 1900s, we would call it fanfiction. I don't mean that derisively fwiw. Shakespeare wrote fanfiction too after all, but I don't think The Tragedy of Richard the Third claims to be historically accurate.

As for Stephenson's demise supposedly leading to Broughton's Rules being written, my best guess is that these exaggerated reports stem from the "New Rules of the Ring" of 1838 being written after Owen Swift killed Brighton Bill (William Phelps) in a fight.[[35]] That and/or a literal interpretation of the line "A fatal Blow impressed the Seal of Death" from the poem. And because Broughton's Rules were widely misunderstood to have originated in 1743, Henning had no choice but to move the fight from 1744 to 1741. I feel kind of bad gunning for Henning since he's been dead for so long and the introduction to his book makes it clear he has a deep admiration for the sport of boxing, but alas, I am a soldier of truth (as much as my times and temperament allow me to be).

Let's finish by going back to the poem though. One thing that will have stuck out to you is that some of the words don't rhyme. Capt. Thompson had the same observation almost 250 years ago: "no Irish Bard would have classed these words together for rhymes, East, vest ;---impel, quill ;---wait, bleat ;---flood, rowed, &c." But nevertheless I still think it's nicely written, even if it does lean somewhat heavily on parodying Virgil's poem Aeneid.

It seems Gymnasiad was saved from complete obscurity by being partially included in The Penguin Book of Eighteenth Century Verse and The New Oxford Book of Eighteenth Century Verse in the latter half of the 20th century, with only the final third of the poem making the cut. The editors of those books decided to scrap the tertiary scribbles too, which I think is a shame, but it does mean that this is another (dubious) PrizeFighting exclusive. We know this to be something.

[[33]]:John Gretton, sometimes spelled Gretting. Referred to as Bill Gretting on CyberBoxingZone for some reason.

[[34]]:Thomas Allen AKA Tom Pipes

[[35]]:Swift himself refers to Broughton's Rules in his 1840 'Hand-Book To Boxing'.

[[36]]:These are of course both the O.S. (Old Style) dates of the Julian Calendar, as they appear written in original sources.

Converted into the New Style dates of the Gregorian Calendar we use today, the first fight was on Thursday April 10th, 1738 and Tuesday May 5th, 1744. Yes, one of the earliest big fights in boxing history took place on Cinco De Mayo.