Comic Review: Last On His Feet - Jack Johnson and the Battle of the Century (2023)

Content Warning: This post discusses depictions of racism, domestic abuse, suicide, and my complaints about how the comic handles them.

The noble art of boxing hasn't had much representation in media of recent decades when compared to its 20th century peak, this includes sequential art. Thankfully though, that doesn't mean comics about boxing don't get made anymore. And of the ones that are made, biographical stories are often a popular choice. Probably because the story is already written.

Jack Johnson's story is definitely an interesting one, becoming the first black heavyweight champion of the world in a society that hated black people is ripe for drama. It's also ripe for imagining how explicitly racist that society would be.

By my count, the n-word, c**n, darky, and simianisations appear at least 50 times. Holy moley, that sure is a lot of racial slurs! You'd be forgiven for thinking this comic was ghostwritten by Uncle Ruckus. If you include the liberal references to slavery/Jim Crow/lynchings/minstrels and all the times Johnson is called 'spook', 'boy', 'smoke', or 'negro', it's averaging one racism every 2 or so pages. You can tell that whoever wrote this had no concerns about my Google Search rankings.

Look, I get it. It'd be doing the past an undue favour to soften the extent and severity of racist abuse in 1910. But at what point does this become gratuitous? I would say after about a dozen pages. The author's note at the start explains that they're taking some creative liberties and I have few qualms with that. It goes onto to say that "we wanted to make this vital American story more available to twenty-first-century audiences".

Not trying to brag but I live in the twenty-first-century. And I was under the impression that copious profanities makes your work less accessible by limiting your potential audience. I realise though that works approaching black suffering, black trauma, and black humiliation are of great interest to... umm.... certain American audiences, so maybe it's just that I'm not the target demographic.

"Johnson" tells the reader on one page that he "can't even repeat the things [Jim Corbett] said during my battle with Jeffries". I shudder to think what was left on the cutting room floor after reading the most direct and unrelenting displays of racism I've ever seen in a comic book, there's a lynching for goodness' sake. A few asterisks would've been welcome since any readers would be able to figure out what's being omitted. I wanted to get this out of the way first. Because it is undoubtedly, and likely by design, the first strong impression the comic makes.

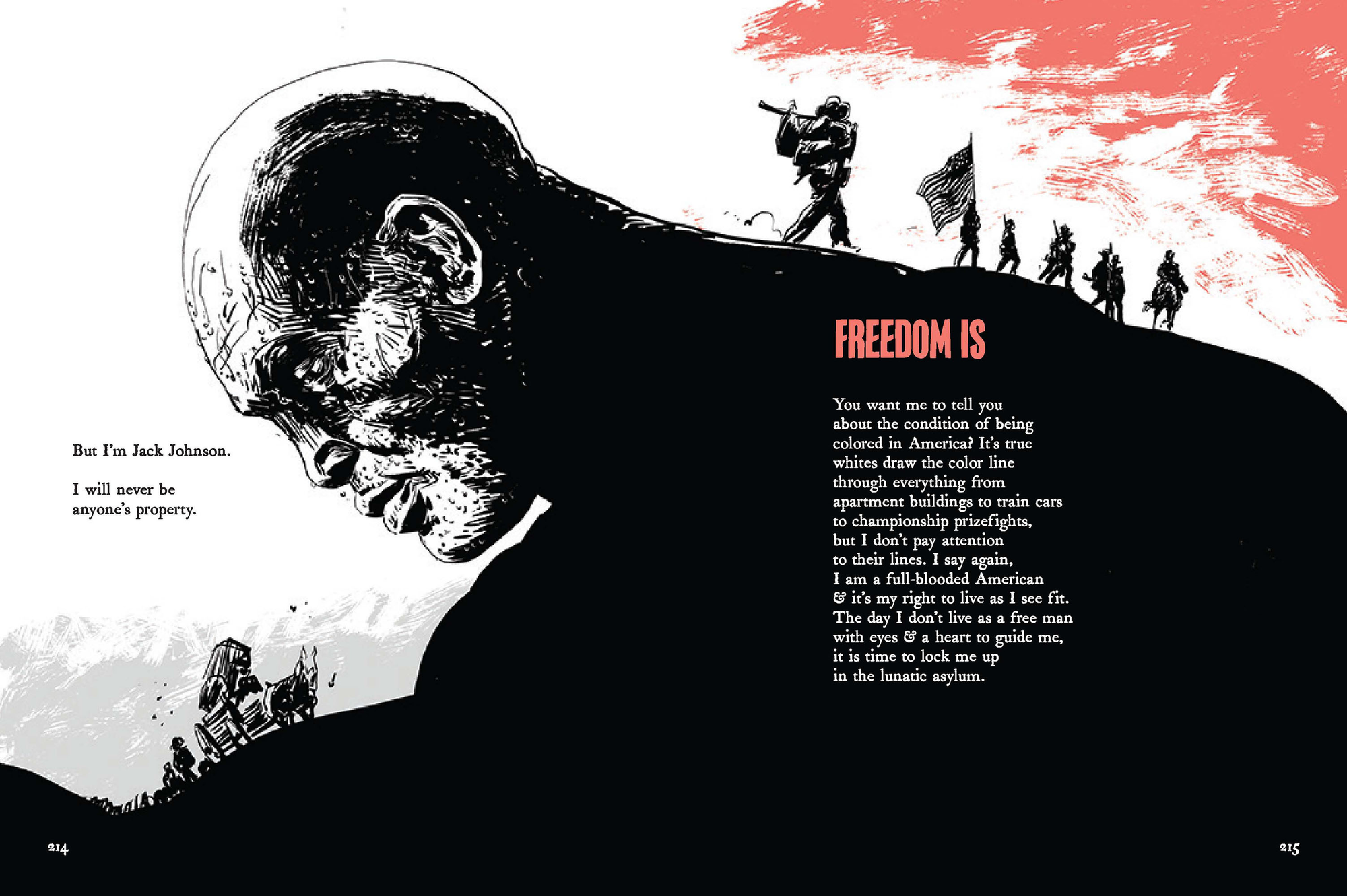

The other unavoidable impression is the muted colour palette - black and white accentuated by splashes of red. Almost like a fight between a black man and a white man accentuated by splashes of blood. The shades of grey also become more pronounced when you pay attention to them. Poetic, isn't it? The credits page even says 'Poetics by' instead of the usual writer's credit. The writer, Adrian Matejka, has won and been nominated for a bunch of things according to his website, including being a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry. I'm convinced he's not bitter about not winning, as I read a comic where a contrived exchange about racing ends with a fourth-wall breaking "second place doesn't pay".

I must admit to being a neophyte when it comes to poetry. But I quite liked some of the ones in this, while the shock value language rolled off me like water off a duck's back, a few of the metaphors woke me up as the narrative jumped around in search of interesting things to focus on. The action takes a while to get going and the closest thing to the first punch being thrown is on page 69. For a moment I thought the first "actual" punch showed up on page 86, but alas it was a meta drawing of a ringside cartoonist capturing the fight. The real fight begins a few pages later. It's hard to discern if this long wait was intentional or unintentional, and if intentional whether that was due to the writer or the artist.

This is Matejka's first comic and he avoids the common pitfall that other outsiders tend to make in their endeavours; a lot of them fail to make the case for why that story needed to be told through the medium of comics. In Last On His Feet, however, there's a fresh mix of poetry blended with archive material and earnest attempts to convey the multimedia zeitgeist of the time through displays of film and cartooning. Several pages would not look out of place if transplanted directly into a poetry anthology, picture book, or poster exhibition. Some of it borders on sounding like a history lesson or class presentation, though I imagine much of it will still be new and intriguing to people.

Which only makes it all the more disappointing that the fighting talk - the challenger calling out the champ, the corner conversation between a fighter and coach, the audience discussions and interjections etc - is absolutely trite. The one-dimensional dialogue clichés on show were pretty dated over 30 years ago. They're so well-worn that any LLM would probably spit them out verbatim without much prodding. Matejka read comics as a kid, and is still a fan of those 1970s childhood comics like Black Panther (presumably Jack Kirby's) and Luke Cage because "they were the only black heroes around". He offers up that his comics dialogue is influenced by the way he discovered it all those decades ago and it shows. The captions and poems are much more modern and appealing to a twenty-first-century individual like me.

The art has its charms too, the strongly-defined faces wear plenty of evocative expressions throughout. It's lovingly rendered period piece too. I just wish the fights were drawn with more energy. The battle of the century feels rather lifeless as their hulking frames spend most of the time wrestling. Some of the panels presumably reference photographs, but since this is a comic retelling there was a lot of room for the explosive art comics are renowned for. It's ultimately a matter of taste and preference, the visuals read like Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées instead of Marvel or DC (complimentary).

A depressing number of boxing champions have been womanisers outside of the home and domestic abusers within it, Jack Johnson was no exception. We see Etta's bruised face, we see Johnson striking her, we see her rest a gun on her head, and we see her blood-spattered suicide note. This is Jack Johnson's biography, so it's not unexpected that the story is from his perspective. Even the framing of the story is that he's recounting his life in 1930s New York.

Yet Etta's role in this narrative is relegated to that familiar plot device of a stock, fridged woman whose death serves to anguish the male protagonist. I counted and in the entire 300-page comic, Mrs. Jack Johnson has about as much dialogue as the 5 pages where Booker T. Washington & W. E. B. DuBois debate each other. The second Mrs. Jack Johnson is even more laconic. The only other dialogue from a woman is a young Ma Johnson asking "what town is that?" when she first reaches Galveston. It's true that this is based on real events. It's also true that making women an afterthought so we could watch the boys do some old-timey racing was a choice someone had to make.

Another instance of revisionism concerns Johnson's views on the color line. We know the familiar story of a hard-working black man being unfairly denied his shot by the powers that be – it's a sympathetic story. Less sympathetic, and likely the reason for its frequent ommission, is Johnson himself upholding the color line when he became champion and denying a fair shot to old foe and "World Colored Heavyweight Champion" Sam Langford. It could have made for biting (and still relevant) social commentary to examine the lack of empathy or righteous anger at racial injustice that some skinfolk display when they get theirs.

Overall, it's a decent (if slightly listless) comic and I would not discourage you from reading it if you find the subject interesting or are a fan of poetry. As much as I wanna hand it to them for making me feel like I learned something, I'm filing it under fiction because even without the author's note I'd know that some of the characterisation and plotting was entirely made-up. And opportunities where that would've been warranted were passed up.

I do not doubt that some would praise it as 'unflinching' for its portrayal of Progressive Era racism, it's the preferred adjective for art about brute violence against minorities, yet I can't shake the feeling that this should've given pause to at least a handful in the editorial process. It's not a comic that I expect to revisit often, if ever, unless they did an expanded & revised edition.

Final Review Scores

In a word: Coarse

In a rap lyric: "Jack Johnson beat white boys and f***ed their women"

In a number: 6.81

In an emoji: 😬

In a paint colour: Stonehenge Greige

'Last On His Feet: Jack Johnson and the Battle of the Century'

Written by Adrian Matejka

Art by Youssef Daoudi

Page count (numbered): 318

Pages of art: 304

ISBN: 9781631495588

February 2023, Liveright Publishing Corporation.

BONUS! - Petty nitpicks and pontifications

- The comic says the attendance for Johnson-Jeffries was 15,760. Other sources list the attendance as 18,020 or 16,528, a couple as high as 22,000 – the supposed capacity of the stadium. The actual attendance was... a mystery. Even if someone did figure out the exact capacity of the wooden amphitheatre from photographs and surviving tickets, it's impossible to know how many people didn't pay the price of admission. The best estimates by my reckoning are those of around (and likely north of) 20,000 since Rickard stood to financially benefit from underreporting the attendance as he did in other fights.

- It made me laugh that the BoxRec page for the fight – which also gives the attendance as 15,760 – refers to Bert Sugar as a "storyteller" in place of a historian because his penchant for untruths was too much for even them to ignore.

- Jack Johnson, like almost every other big/recognisable name in boxing from the 1880s to the 1950s, has had his legend enhanced beyond what it perhaps should be. To the best of my knowledge, the bulk of this push came from the efforts of Nat Fleischer (founder and long-time editor of Ring Magazine), who rated Johnson extremely highly for decades. Sportswriters and raconteurs who followed largely took his word as gospel and accepted the myth as is.

- There's probably a nifty German word for Johnson's oddly balanced legacy, if not for Fleischer exaggerating Johnson's prowess then the near-unanimous hate for him would've continued unabated and Johnson may well have been erased from the heavyweight pantheon that he's now a mainstay of.

- In my light research, I came across this amusing cope from John L. Sullivan, where he's afraid to pick a winner in a New York Times article from July 4, 1910, the day of the fight: "Understand. I am not afraid to pick a winner. I never have been. Sometimes I have been right and sometimes I have been wrong. There would not be anything to prizefighting if I could pick winners in every fight. The reason that I haven't come out with my choice in this affair is because I have not any logical reason for my decision. It is just like one of those woman things — I just feel it, and that's all."

- And on the front page the next day? "You will deduce from the foregoing that I really had picked Johnson as the winner. My personal friends all know it. [...] the fact remains that three weeks ago I picked Johnson to win. It seems almost too much to say, but I did say inside of fifteen rounds."

- It's only just occured to me that Johnson-Jeffries happened on a Monday.

- I'm not holding it against the creators of this comic specifically but it'd be nice to get more stories about figures that haven't been covered in great detail. The bibliography for this comic was one and a half pages long. There are unappreciated stories waiting to be told, folks.

- About half-way through writing this I remembered that I forgot to use headers. I think the piece turned out alright though?

- The gun that Etta uses to end her life in the comic is a Browning FN M1910. I don't know much about guns. I suspect the artist (who hails from France) doesn't either, as it's the first result on Google when you search '1910 gun'.

- Newspaper reports from the time specify that the actual gun was a revolver. There was a coroner's inquest which may have mentioned a specific model, but I had no luck finding it on the few publicly available online archives.

- The police that arrest Johnson in 1913 under the Mann Act drive a 1920s Ford Model T with a sheriff star on the side, because the 1920s Model T is the one that comes up when you search for that iconic 1910s car. The rifles that the coppers carry are Winchester Model 1910's because you already know why.

- It doesn't take much digging to find that police back then used different cars and primarily relied on clubs or revolvers as their weapon of choice.

- The lynching panels, representing a flashback to the post-fight race riots, were modelled on a photo of George Meadows, who was lynched in Alabama in 1889.

- No points for guessing why this photo, which is used on the Wikipedia page for lynchings, was used as a reference.

- "Johnson" at one point says "I am six foot, two inches tall & I weigh two hundred & fifty pounds", which is more in line with modern heavyweights than contemporary reports.

- Imma press X to doubt on a stoic Jim Jeffries entering the ring and demanding from the crowd that no harm befalls Johnson if he wins.

- You may recall that in 2020 after racial unrest in the world's hegemon, one of the placations offered in place of institutional/systemic reform was to capitalise the letter 'b' in 'Black', as is done with identifiers such as Latino, Asian American and Native American. Well-meaning and a tad performative; this comic is fully on board with the decision.

- BLACK should be All Caps

- No thematic puns allowed in this review, this isn't IGN.

- A few of the drawings feel like caricatures that you could precede with a not very nice adjective.

- The writer really likes the phrase "fistic science".

- In addition to Mrs. Johnson, Mrs. Johnson, and Mrs. Johnson, there is one more woman who gets a speech bubble. An unnamed lady says "Hu hu hu!" in response to being flirted with.

- Thomas Hauser noticed that the comic refers to President Roosevelt instead of President Taft, an anachronism that I missed.

- He also picked up on the color line and Johnson's own discomforting views on race, though failed to namedrop Sam Langford.

- It's worth bringing up one last time to really belabour the point - there are too many slurs in this comic. I have thick skin but it's clear to me that this could be really upsetting for some kinfolk. It's the volume and also how needlessly dropped in they feel, like sprinkling in shock value for flavour. It's comparable to how many you'd expect in Richard Pryor's comedy, an episode of The Boondocks, or historical texts from slavery/colonial times - except without the social commentary, political satire, or educational value.