A Tale of Two Stoppages

On Saturday's card we saw Kholmatov-Ford and Lopez-Abe both end in TKOs after referee interventions. Were these the right decisions?

Lopez-Abe

Abe Reiya showed a lot of heart as Japanese fighters often do. By the end of only the second round, his right eye was swelling almost completely shut after an accidental illegal blow by the unorthodox and awkward Lopez. The ringside physician became a staple of the corner alongside the coach, chief second, and a cutman armed with an overmatched enswell. The referee rightly observed that it wouldn't get better by the end of the night. A freelance translator also got involved as things became more hectic on the ring apron. It is of course right to be concerned about impaired vision in a contest where sight is pretty important when it comes to avoiding punches, but were these concerns overblown? Abe was able to see out of his bad eye and they sensibly decided to monitor how things progressed. His eye didn't get better, but it didn't get much worse. Lopez was up on the scorecards but it would be an exaggeration to call it a completely dominant performance. And as the rounds went by, Abe moved/ran more as Lopez struggled to find his range and became less accurate. Until round 8, where Lopez threw a flurry of punches (most of which did not score) but referee Mark Nelson felt compelled to call a halt to the action.

Abe was likely going to lose if it went the full 12, but this was apparent at the end of the 2nd round. Why stop it early in the 8th instead of seeing out the remaining 15 minutes?

Kholmatov-Ford

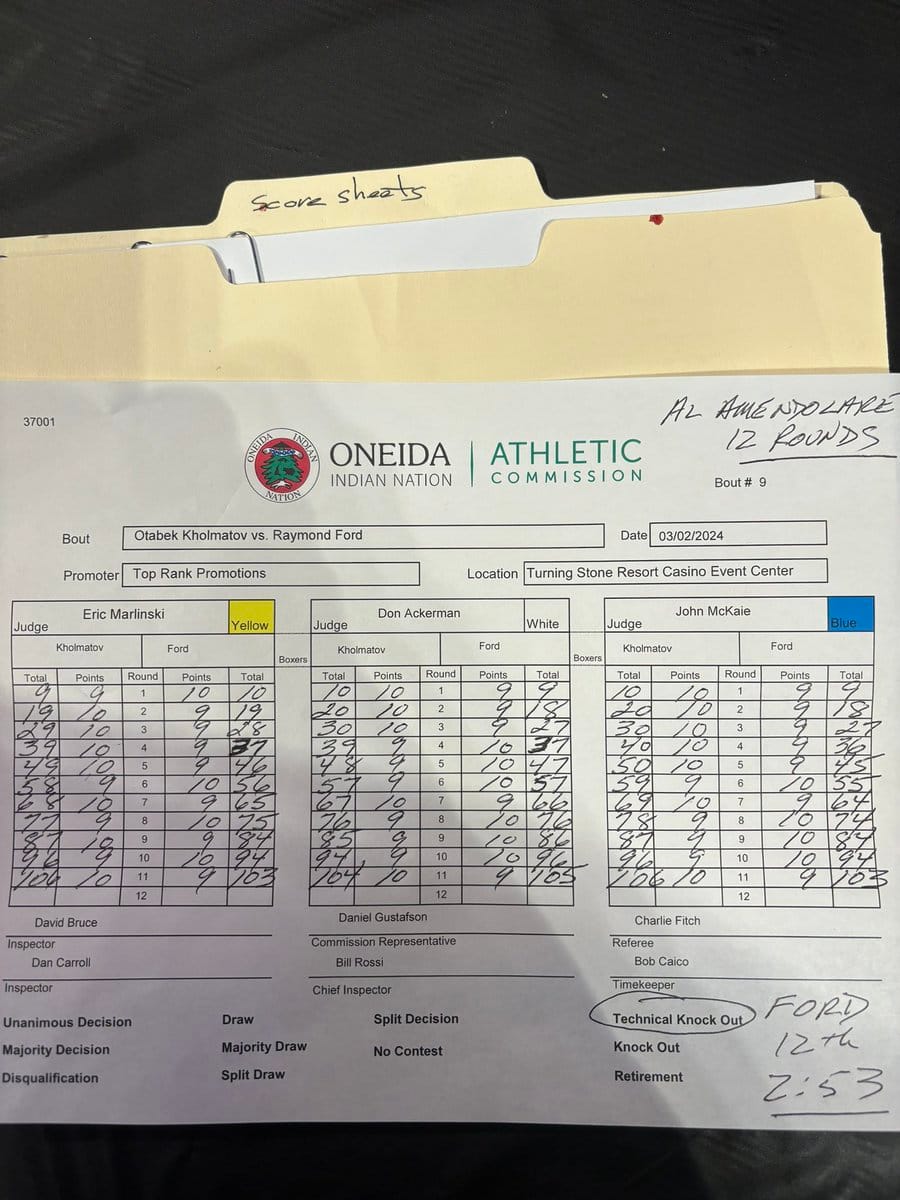

Raymond Ford was losing 106-103 on two scorecards going into the 12th and final round against Otabek Kholmatov. This meant that Ford needed a knockout to win (or to score two knockdowns to get a 10-7 round and a majority decision win). I wasn't scoring the whole fight though I thought Ford should've got the nod on the 11th even after rewatching it. Ford received a nasty cut under the eye after a clash of heads, for whatever reason the referee didn't call it as a headbutt until a full minute after it happened. It's always tough to look at someone who's bleeding that much and say that they won but in any case all three judges disagreed with my assessment. Who knows if the judges would've seen it differently if it was called as a headbutt right away? Much more of the discourse has been about the 12th.

Kholmatov got caught and was on shaky legs with just over 30 seconds left. He was similarly stunned at the end of the 10th but saw out the round as Ford didn't press forward. Ford would not repeat the mistake. He chased a retreating Kholmatov and sent him flying into the ropes with a jab. Technically, if a fighter is prevented from going down by the ropes then it should be called as a knockdown. Kholmatov bounced back off the ropes and fell down after some wrestling, which was rightly called no knockdown. With 10 seconds left, another right hand sent Kholmatov crashing into the ropes again. Only this time the referee waved the fight off entirely. Shades of the Chavez-Taylor stoppage. Though not as dramatic as that miscarriage of justice, Saturday's was more egregious. The ref ruling a knockdown would've only cost Kholmatov some pride as he had done enough to win even if he had conceded a 10-8 round.

What's in a punch?

One punch can change everything in a boxing match. It could launch a career as easily as it could derail a life. Anyone involved in boxing, including the viewer, explicitly accepts and condones this. So why the squeamishness? The flurry that Lopez threw against Abe and Ford's right that dazed Kholmatov were practically as dangerous as the opening exchanges of their respective first rounds. Some would argue they were vulnerable in those closing moments but this only highlights another perception fallacy: the idea of an invulnerable fighter.

Had Abe's eye not swollen and Kholmatov's legs not buckled then they could well have gone the distance relatively unmarked. However, the wear-and-tear from all those rounds of getting hit in the head would still exist beneath the surface. Out of sight, out of mind. You know this, the fighters know this, and the referees should know this. The fighters have already accepted this level of risk, as has everyone else who is party to it. Withdrawing consent at the worst time is not done in the interest of fighters, it's done in the interest of avoiding a guilty conscience. Denying those who have already taken risks and made sacrifices is necessary sometimes, but sometimes it feels like cheating someone for no good reason. It's disingenuous to be afraid that the next punch could be really dangerous when the first punch should scare you just as much.

"Anything could happen" should not only be seen with a negative connotation.